On a subject sort of relevant to my last post of 2013 here, last week the Pew Research people released the results of an international survey that they’ve been conducting for the past few years. Their basic findings, in very simple terms: The more money people have in their pockets, the less they see religious belief to be a precondition for moral goodness. The United States would seem to be an exceptional case in this study, but on closer examination it’s really not.

So who should be excited, threatened or disturbed by these findings?

These results actually shouldn’t come as a surprise in any particular sense, nor should the fact that the United States once again appears to be an exception to the rules of secularism laid out in some of the more problematic reporting on this matter, nor should the fact that the polemics tend to snowball the further from the facts you get on this issue.

These results actually shouldn’t come as a surprise in any particular sense, nor should the fact that the United States once again appears to be an exception to the rules of secularism laid out in some of the more problematic reporting on this matter, nor should the fact that the polemics tend to snowball the further from the facts you get on this issue.

First of all let me clarify what I see as the primary non sequitur related to this question: It is not asking how many people believe in God (large or small g), or how such beliefs affect their own lives. What it is effectively asking is, can you actually trust someone who doesn’t believe in any god to still be a good person? In that regard it actually has very little to do with personal faith as such. Pope Francis and I are both strong believers in God, but we are both entirely convinced that the factually correct answer to the survey question is no, you don’t have to believe in God to be a “person of good will” and to treat others with decency. On the other hand, Machiavelli and his followers –– and among the living, Jürgen Habermas –– while having no particular belief in God themselves, have stated that religious belief plays an essential role in keeping “the masses” in line and enabling productive levels of social cooperation, implying that one should have certain suspicions about those who lack the moral restraint which personal faith tends to instill. So while this is an interesting question on a number of different levels, it really doesn’t measure levels of personal faith in any direct way.

What it does measure, however, is probably more relevant to the issue of “secularization” as it is defined by sociologists than personal faith is: It measures the extent to which religious mutual understanding is socially expected of people as a foundation for mutual trust. The current Wikipedia article on secularization begins by defining the concept as “the transformation of a society from close identification with religious values and institutions toward nonreligious (or irreligious) values and secular institutions.” The sociology section of about.com defines secularization as “a process of social change through which the public influence of religion and religious thinking declines as it is replaced by other ways of explaining reality and regulating social life”. Agreed. In other words what we’re talking about is how much control religion has over society, which is a somewhat different question than the extent to which people personally believe in God.

Peter Berger tells the story of a recently arrived immigrant dentist in the United States starting to work on a new patient’s teeth when the man stopped him briefly to say, “By the way, I’m a Baptist.” The dentist had no idea what relevance this had to the condition of the man’s teeth, or anything else, but for a sociological researcher the message was clear: The patient was saying that he could be trusted to pay his bill afterwards so there should be nothing for the dentist to worry about in that regard; he didn’t want the dentist to be distracted by such concerns while he was working on his teeth. What the new survey results show is that this sort of anecdote could also easily take place in many African or South American countries (perhaps with a different church being named) but among more prosperous “Western” countries it would be unique to the United States. It says nothing about how well Baptists or other believers actually pay their bills, nor about how non-believers in turn attend to their own financial obligations. Nor does it tell us how fervently people believe that some supernatural power holds them responsible for their actions. It only tells us about how people within the society in question use religion as a basis for their social credit rating schemes.

On one level there would be an obvious correlation between how widespread personal faith is and how much people use that as a standard for determining whether or not they can trust each other: Such faith has to be in relatively widespread circulation to be accepted as a form of social capital. By analogy, legend has it that the southern states of the US originally became known as “the land of Dixie” due to the use of a French (or French language) currency in which the ten (dix) was particularly well known. That would not imply any particularly strong allegiance to France or the French economic system, but it would imply at least some sort of cultural connection in France’s direction which related to the means by which Southerners exchanged goods and services. The personal religiosity of people who trust each other on the basis of belief in God need go no deeper than that.

On one level there would be an obvious correlation between how widespread personal faith is and how much people use that as a standard for determining whether or not they can trust each other: Such faith has to be in relatively widespread circulation to be accepted as a form of social capital. By analogy, legend has it that the southern states of the US originally became known as “the land of Dixie” due to the use of a French (or French language) currency in which the ten (dix) was particularly well known. That would not imply any particularly strong allegiance to France or the French economic system, but it would imply at least some sort of cultural connection in France’s direction which related to the means by which Southerners exchanged goods and services. The personal religiosity of people who trust each other on the basis of belief in God need go no deeper than that.

The social mechanism involved comes back to Machiavelli’s strong belief that religion is an essential means which any ruler should take advantage of in order to do his job effectively. While it may not hold true as a general definition for religion, in the vast majority of cases religion comes down to a social expression of belief in God or gods. Taking advantage of this belief as a means of manipulating those under their power can be a very potent tool in the hands of rulers, whether the rulers in question happen to share this belief or not. Thus it remains strongly in the self-interest of the ruling elites to encourage people to believe that there is some divine power out there which is on the rulers’ side on things, and to sow distrust in those who would question the divine basis for the rulers’ authority. From there it would stand to reason that the greater the polarization is between a nation’s lower classes and its rulers, the more critically important it becomes for rulers to have this tool at their disposal so as to reduce the chance of insurrection. It would also stand to reason that the more economically helpless the people feel, the more likely they would be to base their sense of solidarity on transcendent factors like a shared belief in God. In these regards the recent Pew data merely provides empirical evidence in support of what sociologists of religion should have pretty well surmised already.

What this doesn’t tell us is what sort of a role personal faith plays in people’s lives, and whether or not that faith is an overall good thing in terms of social dynamics. It is a major leap of faith to move from the Machiavellian theory that the religious faith of the people provides an important means of manipulating them to the Leninist theory that religious faith can be reduced to nothing more than a means of bourgeois manipulation. That is sort of like saying that because antibiotics are being fed to beef cattle to cause them to put on weight faster (in turn leading to humans consuming their meet also to put on weight faster, which is a very real problem these days, by the way), we can conclude that the only function and purpose of antibiotics is to cause weight gain.

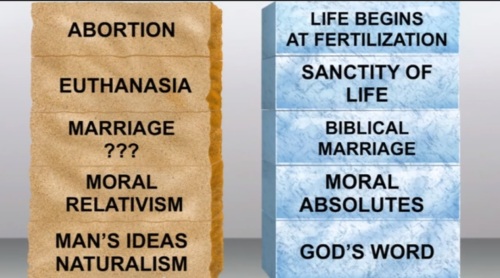

So what is the purpose of Christianity, and perhaps other comparable religions, if not to enable social control of the masses? Quite simply, to teach us to respect each other as fellow beings “made in the image of God,” and to look beyond ourselves for the capacity to live up to ideals we feel that we’re not capable of living up to on our own. I won’t bother to proof-text that out here, but if there are any fundamentalists out there who wish to challenge this summary of the Gospel message as inaccurate I’m up for the debate.

For any atheists and other skeptics who consider this to be too optimistic a summary of the faith meanwhile, I freely acknowledge that many of my co-religionists have rather missed (or misplaced) the point on this one, but that doesn’t make it essentially wrong. The fact that the Bible itself is full of bitter power struggles (especially in the Old Testament, but really in both testaments) doesn’t take away the essential focus of the teaching of Jesus on the points given here –– commonly known as “the twin commandment of love”. The rest of the essential message of Christianity can be mind-mapped back to these two points, not with absolute agreement on all of the details involved, but with essential shared purpose among “people of good will” within the faith and beyond it. Here too I’m quite open to further debate with anyone who cares to question this interpretation.

In any case, once you accept that there is more to religion than what Lenin was prone to acknowledge, much of the polemic against theism in general that we find in CJ Werleman’s summary of the Pew report on AlterNet essentially falls apart. The reasoning he gives for seeing atheists as in fact morally superior to theists –– based on the isolated statistic of atheists making up a disproportionately small segment of the US prison population –– really proves none of the points he is trying to make. What this factoid rather tells us is that self-identifying as an atheist is far more risky and thus much rarer among those in lower economic classes and minority communities in American society who end up as the basic fodder of the prison-industrial complex; whereas among the upper classes, who have all sorts of means of avoiding imprisonment when they commit evil deeds, publicly acknowledged atheism is a far safer posture to hold.

Salon’s republication of Werleman’s article then added sloppiness to the intellectual carelessness of the original by captioning their Facebook link with the quote, “Without the South’s religiosity, ‘America’ would look like a developed, secular country…” and then leaving out the poorly reasoned section of the article containing that quote from the version they posted.

For a more rational heuristic as to what sort of people should be more readily trusted and what sort of people should be kept more at arm’s length, rather than looking at how strongly different groups are represented within prison populations we should be considering the frequency of psychopaths occurring among them. In those regards theists have a far from spotless record, especially given the ways in which theism is susceptible to power abuse, but power-hungry atheists generate at least their fair share of social tensions and monsters to be afraid of.

But the primary lessons to be drawn from the Pew survey aren’t essentially about whether either theists or atheists are inherently better people. It rather shows us something about people’s reluctance to trust those whose foundational ethical assumptions are different from theirs. Most specifically, it invites us to consider why it would be that poorer people around the world are more likely to consider their religion as an important basis for personal trust, and why this tendency would be particularly pronounced in the United States in general and in the former Confederate states in particular.

On significant factor here is the dynamic confirmed by recent studies that the wealthier a person becomes, the greater the risk is of that person losing a capacity for empathy. Thus if religious participation is in many respects an exercise in empathizing with others, it stands to reason that the wealthy will place less importance upon it than those whose empathetic reflexes have not been damaged in this way. This in turn would lead to poorer people having a greater tendency to build contacts with like-minded people through religious activities than rich folks do. Probably a minor factor, but still worth noting.

A far more significant causal factor, I believe, would be a lack of basic education among the poor (not only in the South, but across the US), in civics in particular. This aspect of education involves making learners more aware of those outside of their own closed communities; ideally involving actual mutually respectful contact with people who are part of “other” groups –– those of other skin colors, other language groups, other religious backgrounds, other sexual attractions, other cultural norms, etc. If these “other” people can be kept as a distant abstraction and if authority figures are able to maintain ignorance about such “others” within their isolated communities, that makes hatemongering a far easier process for them. From there they can use that hatred as a means of motivating people to do all sorts of things they may have in mind, or to “take their eye off the ball” as they go about fleecing the suckers. Nor does hatred of the other have to be the result an intentional plot to manipulate the haters; it can be an entirely organic and self-sustaining reaction within ignorant and isolated communities. A brilliant example of this is the ways in which the fictitious Eastern European society in the film Borat looks at Jews.

In this regard the social dynamic we see demonstrated in the recent Pew data is as follows: The better off people are economically, the better educated their children become; the better educated each successive generation is, the less ignorant of and segregated from others they are inclined to be; and the more aware of others they are in practice, the more likely they are to respect those others as individuals regardless of differences in race, religion, language, sexuality, etc. The southern states of the US have their own historical reasons for being somewhat backwards in these regards, but there is no credible sociological argument for reducing religion as a means of improving the situation. Color me optimistic, but I believe that improved civics education, including elements of concrete cross-cultural interaction, can go a long ways in eliminating the toxic prejudicial elements of traditional religious cultures, leaving in place a valuable set of societal resources to be exercised in communities of faith.

Southern “Bible Belt” culture and its various spin-offs are a complex problem unto themselves. Besides Machiavellian strategies historically being used by the white aristocracy of the South to control the poor black folk of the region by way of religion (which majorly backfired on them with the role of Martin Luther King Jr. in the Civil Rights Era), there is a widespread ignorant assumption that white American Protestants have somehow inherited the role of “God’s chosen people” from the ancient Israelites. It is fair to say that Bible Belters are not alone in this regard: many forms of religion irrationally declare divine favor on some in-group at the expense of the human dignity of various out-groups, and that they give religion a bad name in the process. It is also fair to say that this aspect of “Christian culture” runs directly contrary to the teachings of Jesus and the core message of Christianity. This problem needs to be dealt with, but not through the elimination of all religious influences in American culture.

Southern “Bible Belt” culture and its various spin-offs are a complex problem unto themselves. Besides Machiavellian strategies historically being used by the white aristocracy of the South to control the poor black folk of the region by way of religion (which majorly backfired on them with the role of Martin Luther King Jr. in the Civil Rights Era), there is a widespread ignorant assumption that white American Protestants have somehow inherited the role of “God’s chosen people” from the ancient Israelites. It is fair to say that Bible Belters are not alone in this regard: many forms of religion irrationally declare divine favor on some in-group at the expense of the human dignity of various out-groups, and that they give religion a bad name in the process. It is also fair to say that this aspect of “Christian culture” runs directly contrary to the teachings of Jesus and the core message of Christianity. This problem needs to be dealt with, but not through the elimination of all religious influences in American culture.

Besides the photo ops and private conversations with President Obama last week, the most recent headlines regarding Pope Francis have had to do with his recent theological statements confirming a personal belief in hell as a real place where wicked people’s souls go when they die –– Mafiosos in particular. The thing which puts one in the position of deserving eternal torment is not defying the church’s authority as such, but disregarding the rights and dignity of other people –– failing to love in the what Jesus commanded us to. I believe that this sort of “hellfire and brimstone” message, not the moralism and cultural control preached by the “religious right” nor the strict secularism preached by the missionaries of “new atheism”, offers the best hope for curing what ails our failing communities. I challenge any of my readers to try and change my mind on this one.