I first met Finns and became aware of Finland in the mid-1970s, when the country was fifty-some years old. At the time of my first visit to this country in the autumn of 1983 it was still 65. The first Finnish Independence Day that I witnessed in person was when the country turned 69. Today it turns 95 years old. Not only have I had the opportunity to witness nearly 30% of this nation’s history personally, but I’ve had the chance to become personal friends with people who were born here before the nation even became independent. That’s sort of a remarkable thing for a foreigner to stop and think about in an adopted homeland. So in celebrating this country’s aging process today I think I’ll offer a stream of consciousness perspective on the matter from my position as one of this country’s veteran outsiders within already.

If we break up Finnish history into significant eras, I propose that we call them the Mannerheim Era, the Kekkonen Era and the Nokia Era. All of these deserve profound respect both for the named leadership force and the national accomplishments that Finland achieved during these eras. All of them deserve to be looked at critically for the victims they left behind.

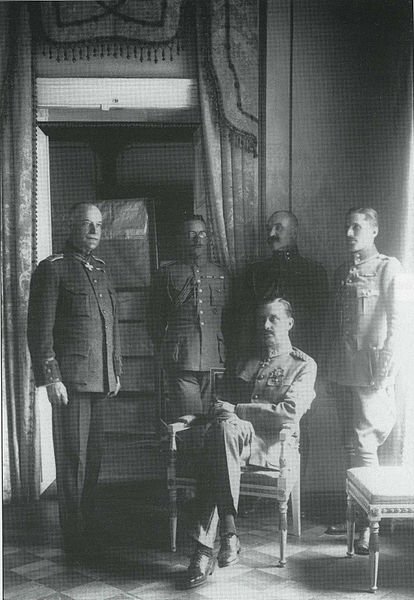

The Mannerheim Era of Finnish history can be designated as the time running from Finland’s struggles to establish an independent identity in 1917 through the direct aftermath of World War 2. Field Marshal C. G. E. Mannerheim, as he is still most commonly and respectfully known, resigned as president of Finland in 1946 due to old age and ill health. He died in 1951, in Switzerland, at 83 years old. My closest connection with him was that when I first moved to Finland I worked with his grandson at the McDonalds on the street named after him in Helsinki.

Mannerheim was considered by many to be a conservative’s conservative in every sense: promoting rugged individualism, libertarian personal autonomy, the right of the rich to remain rich and the role of a strong military in enforcing these principles. Historians are divided on the question of how deep Mannerheim’s personal sympathies for the Tsar ran, and how willing he would have been to keep the Russian empire going in Finland, but he clearly saw the writing on the wall before it fell, and by the time of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia he was well positioned to lead an autonomous force representing the interests of Finland’s bourgeoisie against Lenin’s revolution spreading into this part of the empire. It was because of Mannerheim’s military acumen that, in the civil war that followed Finland’s declaration of independence, the country did not become a communist country. The Red Armies were soundly defeated and in the aftermath many of their supporters died in POW camps. Finland thus started out its history as a deeply divided country.

Mannerheim was actually independent Finland’s second official head of state, holding the title of “regent” in 1918 and 1919. While Mannerheim was still busy fighting the Reds a fellow ironically named Svinhufvud (Swedish for “pig head”) officially held down the administrative side of things for him. A little known fact of history is that briefly during this period Finland was officially a kingdom, with a minor German prince appointed to the role of King. But the two month “reign” of Finland’s “Charles I” saw the defeat of his native Germany in World War I, and rumors are that he tried to study the language that his subjects spoke and the weather conditions they lived under, so he soon decided it wouldn’t be worth the trouble. He abdicated his throne without ever setting foot in his kingdom or actually trying on his crown. Rather than a king, Mannerheim had to break in a president of Finland as a republic as the next head of state.

Back in Russia there were rumors that Mannerheim and his cronies lacked the support of the common people, and that if the heirs of the defeated Finnish Reds were given sufficient tactical support they could take over the country and gladly join into the Soviet Union’s bold social experiment. Whether this was a widely held belief among Stalin’s inner circle or whether this was just a convenient propaganda excuse for expansionism, in December of 1939 it was acted upon. The Soviets appointed a Finnish government in exile in the town of Terijoki and proceeded to attempt to assist them in assuming their “rightful authority” over their nation. This is what is known as the Winter War, where approximately 1000 Finnish civilians died in Soviet air attacks, about 26,000 Finnish soldiers were killed in battle and the tiny Finnish army lost most of its tanks and aircraft; but under Mannerheim’s ingenious leadership again they succeeded in holding off an invasion force more than ten times their size, with hundreds of times more equipment, proving decisively that there was no popular sympathy among the Finns for the idea of becoming Soviet citizens.

Finland was still the official loser of this 3½ month conflict, and the resulting peace did not hold. Mannerheim decided to form a tentative alliance with the Nazis in pushing back Russian advances, which restored some Finnish pride but in the long term may have done more harm than good. When all was said and done, against all odds, Finland still had its pride and independence, but its losses were by every measure far greater than what the Arab states lost at the hands of the British with the founding of Israel. As the Palestinian question was to the Arabs, so the Karelian question became for the Finns a matter of existential purpose to correct the injustices done to them… only not quite.

Enter the Kekkonen Era. Urho Kalevi Kekkonen fought as a teenager in the White Army, under Mannerheim, in Finland’s Civil War. In the 1930s he went from being a hotshot young lawyer to being a member of parliament, and he quickly rose through the political ranks, holding many ministerial level positions by the time war broke out. Kekkonen was conspicuously bald from a young age, and had distinctively thick eyeglasses, but in every other way he was the very image of machismo. His political base was among the agrarian Center Party supporters, but he pulled in support from many sides of the spectrum with his personal charisma. Yet for many Kekkonen was, for better and for worse, Finland’s equivalent of “Tricky Dick” Nixon, only considerably more successful at the games he played.

Kekkonen’s influence was already noticeable in the Mannerheim Era. In the ten years between Mannerheim’s retirement and Kekkonen’s presidency, the latter served varyingly as Minister of the Interior, Minister of Justice, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of Finland, Speaker of the Parliament and Prime Minister. The big question was, how would Finland deal with the new reality of being a securely independent country, but living under the shadow of a nuclear armed Soviet Union that no Western country was going to step in to protect them from? Kekkonen turned out to be the strategic master of dealing with this tricky problem. In turns he could suck up like the best of them, do tough guy posturing, play good ole boy drinking games with power brokers and find brilliant bureaucratic excuses for screwing over his opponents. It was just before Kekkonen became president, and reportedly as a result of Kekkonen’s wheeling and dealing, that Porkkala, the coastal area west of Helsinki which had been involuntarily leased to the Soviet Union as a navy base for 50 years starting in 1944, was returned to Finnish control, less than a quarter of the way into the lease.

Kekkonen’s influence was already noticeable in the Mannerheim Era. In the ten years between Mannerheim’s retirement and Kekkonen’s presidency, the latter served varyingly as Minister of the Interior, Minister of Justice, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of Finland, Speaker of the Parliament and Prime Minister. The big question was, how would Finland deal with the new reality of being a securely independent country, but living under the shadow of a nuclear armed Soviet Union that no Western country was going to step in to protect them from? Kekkonen turned out to be the strategic master of dealing with this tricky problem. In turns he could suck up like the best of them, do tough guy posturing, play good ole boy drinking games with power brokers and find brilliant bureaucratic excuses for screwing over his opponents. It was just before Kekkonen became president, and reportedly as a result of Kekkonen’s wheeling and dealing, that Porkkala, the coastal area west of Helsinki which had been involuntarily leased to the Soviet Union as a navy base for 50 years starting in 1944, was returned to Finnish control, less than a quarter of the way into the lease.

During Kekkonen’s time the term “Finlandization” came to be used for any country that did what its big powerful neighbor told it to in exchange for not getting stomped on. That was probably never a fair accusation, but to say that the Cold War was a tense time for Finland would still be a significant understatement. Yet during this period of history dominated by Kekkonen Finland successfully hosted a summer Olympics, gained an international following in architecture and design, went from being a primitive agricultural to an advanced technological nation, initiated educational reforms which (only in the 1970s) gave every child a right to a high school education and egalitarian access to a university education, and established their country as one of the primary gateways and buffer zones between the Eastern bloc and the West. It could be said that these advances were gained at the expense of some basic freedoms and on conditions of self-censorship, but recent history in other parts of the world has shown how relative such freedoms can be at times.

Kekkonen’s reign was in many ways quasi-dictatorial. Some jokingly referred to Finland under his authority as “Kekko-slovakia”. He negotiated the broad outlines of economic and foreign policy with the Kremlin, he appointed a small army of bureaucrats to finalize the details, and he made sure that everyone basically did what he told them to. For 25 years that how things worked in Finland. But things were continuously getting better for the peasants, so no one really complained too loudly. Finland never got Karelia back, but other than that things were steadily going in the right direction.

When Kekkonen reached his late 70s, however, it became clear that he had been covering up some Alzheimer’s and other little problems for some time, and so in October of 1981 he semi-voluntarily resigned as president and retired. His last prime minister, Mauno Koivisto, whom Kekkonen had unsuccessfully attempted to fire in his final days in office, took over as the ninth president of Finland.

Koivisto was strong enough to stand up to the aging and delusional Kekkonen, and for that he has earned an important place in Finnish history, but beyond that Koivisto’s greatest show of strength was in his willingness to be weak. During Koivisto’s administration the office of President of Finland started in a process of decline from being one of the more significant de facto dictatorships of Eastern Europe to being the rough equivalent in power to the king of Sweden, only without the wealth and job security that a monarch has. Thus the era following Kekkonen’s can’t really be attributed to any politician, but rather a corporation that in many regards has taken over the country: Nokia.

The Nokia Corporation is named for a grimy little suburb of Tampere, one of Finland’s older inland industrial centers. Where the name of the town came from is unknown, but it could well be related to the word noki: Finnish for soot. When the Finns were required to pay war reparations to the Soviets the creditors demanded payment in durable goods rather than currency, and two of the commodities that they demanded were rubber products (boots and tires) and copper cable. To meet these demands the Finnish government turned to a little company in Nokia which was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy and gave them this massive public contract. By the time that this “debt” was paid off in the late 60s Nokia had become an international household name in boots, tires and electronics. In the 80s, when I first arrived in Finland, they had evolved into an overly diversified consumer goods manufacturer, making radios, televisions, telephones, stereo systems, kitchen wear, everything rubberized… and starting to dabble in IBM clone personal computers. But later in the 80s they made a profoundly wise decision: they should focus their corporate energies on one product line in which they had a significant head start in research and development over most of their international rivals: hand-held mobile telephones. The rest is history.

The Nokia Corporation is named for a grimy little suburb of Tampere, one of Finland’s older inland industrial centers. Where the name of the town came from is unknown, but it could well be related to the word noki: Finnish for soot. When the Finns were required to pay war reparations to the Soviets the creditors demanded payment in durable goods rather than currency, and two of the commodities that they demanded were rubber products (boots and tires) and copper cable. To meet these demands the Finnish government turned to a little company in Nokia which was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy and gave them this massive public contract. By the time that this “debt” was paid off in the late 60s Nokia had become an international household name in boots, tires and electronics. In the 80s, when I first arrived in Finland, they had evolved into an overly diversified consumer goods manufacturer, making radios, televisions, telephones, stereo systems, kitchen wear, everything rubberized… and starting to dabble in IBM clone personal computers. But later in the 80s they made a profoundly wise decision: they should focus their corporate energies on one product line in which they had a significant head start in research and development over most of their international rivals: hand-held mobile telephones. The rest is history.

In fact the expansion of the Nokia Corporation in mobile communications began as the center piece of the Kekkonen legacy –– a successful relationship with the Soviet Union –– was definitively collapsing. In 1987 Mikhail Gorbachev was taken by surprise in a public gathering by having a Nokia mobile handset given to him with his communications minister on the other end of the line. The Soviet leader being wowed by this new technology was a major PR coup for the company. Within five years, arguably thanks to Gorbachev on both accounts, the Soviet Union had collapsed and Nokia mobile phones had taken off like a rocket.

In the deep economic depression that hit Finland in the early 90s, with the collapse of bilateral goods-for-goods trade with communist countries, Nokia and its spin-offs and subcontractors were the one bright spot on the Finnish economic scene. They became one of the most important contributors to tax coffers and political campaigns, and they started getting pretty much whatever they wanted in terms of legislative action. Nokia played no small role in convincing Finns to become part of the European Union and the Euro currency zone. They got major university technology departments started to feed them a fresh supply of bright young engineers specialized in their areas of R&D interest. They even got the Finnish parliament to grant them legal rights to spy on their employees’ e-mail. They’ve actually had a really good run in many regards.

But like the Mannerheim Era and the Kekkonen Era, the Nokia Era of Finnish history might be starting to fade. Since Apple got into the cell phone business the competitive environment has not been the same; and even if they make a remarkable comeback, it is unlikely that things will ever be as good for Nokia again. It remains to be seen whether or not Finland can continue on the remarkable growth trajectory that these first three eras of its national history have delivered. Can the Finnish school system –– initiated under Mannerheim, universalized under Kekkonen and made exceptional under Nokia –– continue to lead the world in generations to come without some new economic miracle corporation to back it up? Or will an internationalist orientation, a cultural emphasis on increased knowledge and a proud heritage of continually facing difficult circumstances and overcoming them regardless continue to serve the Finns well regardless of what global market conditions throw their way?

In my adopted homeland, as in the land of my birth, there are many things I can be thankful for in recent history, but many areas of concern where I can only hope and pray for the best in years to come. This being the holiday that it is though, it is best to focus on the thankfulness side of things. So join me in raising the toast: To the proud Republic of Finland! May her future continue to be brighter than her past!